To

cope with the possibility that terrorists might someday

detonate a nuclear bomb on American soil, the federal

government is reviving a scientific art that was lost

after the cold war: fallout analysis. To

cope with the possibility that terrorists might someday

detonate a nuclear bomb on American soil, the federal

government is reviving a scientific art that was lost

after the cold war: fallout analysis.

The goal, officials and weapons experts

both inside and outside the government say, is to figure

out quickly who exploded such a bomb and where the

nuclear material came from. That would clarify the

options for striking back. Officials also hope that if

terrorists know a bomb can be traced, they will be less

likely to try to use one.

In a secretive effort that began five

years ago but whose outlines are just now becoming

known, the government's network of weapons laboratories

is hiring new experts, calling in old-timers, dusting

off data and holding drills to sharpen its ability to do

what is euphemistically known as nuclear attribution or

post-event forensics.

It is also building robots that would

go into an affected area and take radioactive samples,

as well as field stations that would dilute dangerous

material for safe shipment to national laboratories.

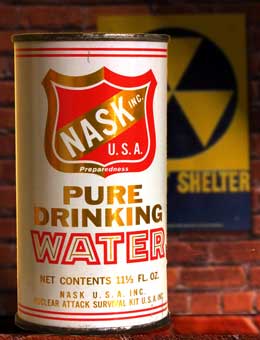

|

| Predicted fallout

developed during cold war. Displays prevailing

wind patterns. |

"Certainly, there's a frightening

aspect in all of this," said Charles B. Richardson, the

project leader for nuclear identification research at

the Sandia National Laboratories in Albuquerque. "But

we're putting all these things together with the hope

that they'll never have to be used."

Most experts say the risk of a

terrorist nuclear attack is low but no longer

unthinkable, given the spread of material and know-how

around the globe.

Dr. Jay C. Davis, a nuclear scientist

who in 1999 helped found the Pentagon's part of the

governmentwide effort, said the precautions would "pay

huge dividends after the event, both in terms of the

ability to identify the bad actor and in terms of

establishing public trust."

In a nuclear crisis, Dr. Davis added,

the identification effort would be vital in "dealing

with the desire for instant gratification through

vengeance."

Vice

President Dick Cheney was briefed on the program last

fall, Dr. Davis said. The National Security Council

coordinates the work among a dozen or so federal

agencies. Vice

President Dick Cheney was briefed on the program last

fall, Dr. Davis said. The National Security Council

coordinates the work among a dozen or so federal

agencies.

The basic science relies on faint

clues — tiny bits of radioactive fallout, often

invisible to the eye, that under intense scrutiny can

reveal distinctive signatures. Such wisps of evidence

can help identify an exploded bomb's type and

characteristics, including its country of origin.

Solving the nuclear whodunit could

take much more information, including hard-won law

enforcement clues and good intelligence on foreign

nuclear arms and terrorist groups. For that reason,

several federal agencies are involved in the program,

among them the Department of Homeland Security and the

Federal Bureau of Investigation.

The program addresses true nuclear

weapons as well as so-called dirty bombs, ordinary

explosives that spew radioactive debris.

"It's a very hard job," said William

Happer, a physicist at Princeton who led a panel that

evaluated the identification work.

|

| A radiation

dosimeter to monitor your total exposure to your

person. Everyone should have one of these,

although good ones are not cheap. Plan on spending

$200-$300. |

Mr. Happer said he was worried that a

rush for retribution after a nuclear attack might cut

short the time needed for careful analysis. "If we lose

a city," he said, "we might not wait around that long."

The effort to fingerprint domestic

nuclear blasts is part of a larger federal project to

strengthen the nation's overall defenses against

unconventional terrorist threats. Mostly, the goal is

prevention. For instance, the government recently sent

teams of scientists with hidden radiation detectors to

check major American cities for signs that terrorists

might be preparing to detonate radiological bombs.

In contrast, the identification

program seeks to increase the government's knowledge and

options should prevention fail. "We're trying to

resurrect some of our capability," said Reid Worlton, a

retired nuclear scientist from the Los Alamos weapons

laboratory in New Mexico who has been called in to aid

the fallout endeavor. "It sort of died. They're not

doing radiochemistry on nuclear tests anymore, so it's

hard to keep these people around."

The effort draws on work that began at

the dawn of the atomic era. Scientists working on the

Manhattan Project built an array of devices to monitor

nuclear blasts in the New Mexico desert in July 1945 and

at Hiroshima and Nagasaki a month later. The experience

helped scientists learn what to look for.

The

first hunt zeroed in on the Soviet Union. In the late

1940's, military weather planes used paper filters to

gather dust particles around the periphery of Russia,

and scientists in the United States who analyzed the

data at first sounded dozens of false alarms, said

Jeffrey T. Richelson, an intelligence expert in

Washington. The

first hunt zeroed in on the Soviet Union. In the late

1940's, military weather planes used paper filters to

gather dust particles around the periphery of Russia,

and scientists in the United States who analyzed the

data at first sounded dozens of false alarms, said

Jeffrey T. Richelson, an intelligence expert in

Washington.

Then, on Sept. 3, 1949, a weather

plane flying from Japan to Alaska picked up a slew of

atomic particles. "That was the real thing," Mr.

Richelson said. Twenty days later, President Harry S.

Truman announced that the Soviets had exploded their

first nuclear device.

The ranks of fallout investigators

swelled during the cold war as foreign nations conducted

hundreds of atmospheric nuclear tests. By all accounts,

the sleuths made many important discoveries about the

nature and design of foreign nuclear arms.

In time, the ranks dwindled as more

and more nations decided to move their test explosions

underground, eliminating fallout. The last nuclear blast

to pummel the earth's atmosphere was in 1980, and the

last known underground test, conducted by Pakistan, was

in 1998.

As the terrorist threat rose in the

1990's, the government began to consider the quandary

that would arise if a nuclear weapon exploded on

American soil. In 1999, Dr. Davis, then head of the

Defense Threat Reduction Agency at the Pentagon, began

an effort to address the identification problem by

financing research at the nation's weapons laboratories,

many of them run by the Energy Department.

The first money came in late 2000, Dr.

Davis said, and the attacks of September 2001 "made it

clear that a very organized event on a large scale was

credible." That perception, he said, helped the effort

expand.

The secretive work won rare public

praise in a June 2002 report ("Making the Nation Safer")

from the National Research Council of the National

Academies, the country's leading scientific advisory

group. Having the ability to find out who launched a

domestic nuclear strike, the report said, could deter

attackers and bolster threats of retaliation. The report

urged that the program go into operation "as quickly as

practical" and that the government publicly declare its

existence.

Since then, weapons laboratories and

other federal agencies have worked hard on the problem.

"They're making progress but they've got a ways to go,"

said Mr. Worlton, the retired Los Alamos scientist.

In a drill this year, dozens of

federal experts in fallout analysis met at the Sandia

laboratories in Albuquerque to study a simulated

terrorist nuclear blast. Mr. Worlton said they were

broken into teams and given radiological data from two

old American nuclear tests, whose identities remained

hidden, and were instructed to try to name them. Some

teams succeeded, he said.

Mr. Richardson of Sandia said the

laboratory was developing a land robot that could roll

up to 10 miles to sample fallout and return it to human

operators for analysis. It could also radio back some

results if it became stuck. Mr. Richardson said the

robots, now in development, are to be ready in a couple

of years.

Experts say a new aircraft for

atmospheric sampling of nuclear fallout is also in

development. The Air Force currently has one, the

WC-135W Constant Phoenix, for such work. It was first

deployed in 1965.

Weapons experts say getting samples

fast is important because some radioactive debris can

decay rapidly. If captured quickly, they can shed light

on a weapon's design.

One way of trying to identify a bomb's

origin positively, several experts say, is to match

debris signatures with libraries of classified data

about nuclear arms around the world, including old

fallout signatures and more direct intelligence about

bomb types, characteristics and construction materials.

"If you're talking about a stolen

device, you might try to do that," Mr. Richardson said.

"But if it's improvised, that's less likely to work. It

might not look like things you've seen before."

A further complication is that even

knowing who made a bomb may say little about who

detonated it. In a 1991 Tom Clancy novel, "The Sum of

All Fears," Islamic terrorists find and rebuild an

Israeli nuclear weapon and set it off at the Super Bowl.

Federal experts say complex threat

scenarios (for instance, an American warhead being

stolen and detonated in an American city) mean that many

types of intelligence might be needed for successful

identification. Over all, it is unclear how much money

the government is spending on the effort.

Private experts offered suggestions

for improvement. Dr. Happer of Princeton, who heads a

university board that helps oversee campus research,

said the program might be cooperating too little with

nuclear allies. "It's to our advantage," he said, "for

all of us to share."

Dr. Davis, the former head of the

Defense Threat Reduction Agency, made several policy

recommendations last April in an article for The Journal

of Homeland Security. He said the F.B.I. should lead the

program, presidentially appointed overseers should guide

it, goals should be set for how long analyses should

take and legal issues of prosecution should be examined.

In an interview, Dr. Davis said his

suggestions had made little headway, partly because of

the topic's grisly nature. "This is an ugly subject

because your best effort is going to be barely

adequate," he said. "That's not the kind of phrase

people like to hear."

Mr. Richardson of Sandia said that the

attribution effort had made good technical progress and

had already some ability to identify an attacker.

"We're hoping for deterrence," he

said. "We don't want anybody to think they can get away

with it."

See my

Radiation Detection info page

|