The

production of smart munitions may be jeopardized by

instability in the battery manufacturing sector, Army

officials fear. Although batteries often are not viewed

as critical components, some munitions programs have

been delayed because of battery problems, experts said.

Developers of smart munitions generally turn most of

their attention to the warhead, the guidance system or

the propellant, but not to the batteries.

The

production of smart munitions may be jeopardized by

instability in the battery manufacturing sector, Army

officials fear. Although batteries often are not viewed

as critical components, some munitions programs have

been delayed because of battery problems, experts said.

Developers of smart munitions generally turn most of

their attention to the warhead, the guidance system or

the propellant, but not to the batteries.

The Commerce Department recently

completed an industry study focused on the niche market

for tiny, but complicated batteries that power

munitions, such as artillery rounds. Details of the

report are unavailable, partly because it contains

proprietary data on manufacturers.

"All I can say is that there is

some concern," said Allan Goldberg, a battery program

official at the Army Research Lab- oratory. "You have a

limited industrial base and a limited number of

purchases," he told National Defense Magazine. During

the Vietnam War, he said, the United States was

producing a million artillery batteries a month. Now,

200,000 batteries are considered a "big buy."

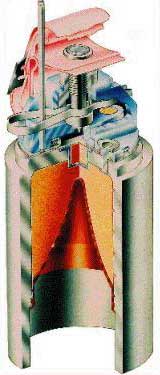

For each of the two main types of

munition batteries--liquid electrolyte reserve and

thermal batteries--there are only two or three

manufacturers. According to Goldberg, the only makers of

liquid electrolyte batteries are Alliant Techsystems in

Horsham, Pa., EaglePicher Technologies in Joplin, Mo.,

and KDI Precision Products in Cincinnati, Ohio. For

thermal batteries, the two manufacturers are EaglePicher

and Enser Corp. in Pinellas Park, Fla.

In a presentation to the Institute

for Defense and Government Advancement conference in

Arlington, Va., Goldberg cited two weapons that were

either delayed or could have been delayed because of

difficulties in manufacturing the batteries. One was the

M-234/235 self-destruct fuze for the dual purpose

improved conventional munitions grenades, and the other

is the battery for the Excalibur artillery round.

At the core of the debate is the

state of the industrial base. Turning to commercial

battery giants isn't an option, said Gold

batteries for all of the Defense Department and Energy

Department munitions applications, are a drop in a very

large bucket compared to commercial battery production,

where one company alone makes 4.2 billion batteries a

year."

One problem is the difficulty of manufacturing such

small batteries. Production line nozzles can clog when

forced to rapidly insert minute amounts of electrolyte

into liquid reserve batteries. These components must

have a quick rise time or the ability to generate power

speedily. "Some rounds may not power up when fired. They

may power up [prematurely] when the sub-munitions are

dispersed," Goldberg said.

Goldberg and others are concerned that the current

sales and profit margins will discourage research into

munitions batteries...at a time when munitions are

growing smaller and smarter, thus demanding more power.

The Commerce Department study came about at the

Army's request. It examined a variety of solutions. "One

permissible recommendation is for the government to step

in and take over these companies," said Goldberg.

"The issue is, are we going to have the small

batteries and small power systems these future systems

will need? The direction we are going with our weapons

systems and our requirements would make us believe that

the expectations for power sources are going to be more

difficult to meet."

Some manufacturers aren't quite as pessimistic. Bill

Harsch, director of market and business development for

EaglePicher, said there are "at least two manufacturers

in each of the [battery] chemistries that are very

stable companies."

However, he readily acknowledges that this is a niche

market. "It's only a $20 million business for us," he

said. In contrast, batteries for conventional Army

missiles alone generate $150 million a year for

EaglePicher. The company makes several types of

batteries for defense and space applications.

"I don't know that there is any incentive to enter

the business," Harsch said. "These [munitions] batteries

are a part of our business, but not a large part of our

business. If we were a small startup company, I'd be

concerned about staying in the business. But we've been

in this since 1952."

Because profit margins are small, Harsch sees little

enticement for research and development. "I think the

people involved are very dedicated... But it's a

constant battle to make money, because the technology is

very, very difficult. And they want very low costs.

There has to be to a lot of development in order to

bring these technologies up to the new specifications."

He

cites problems with the battery for the Army's Excalibur

smart artillery projectile. "There has been an issue

with a rise in voltage rise time. They're really pushing

the envelope of technology. We need to tweak the

design."

He

cites problems with the battery for the Army's Excalibur

smart artillery projectile. "There has been an issue

with a rise in voltage rise time. They're really pushing

the envelope of technology. We need to tweak the

design."

Concerned about the supply of batteries, one fuze

manufacturer produces its own lithium reserve batteries.

KDI manufactures the M234 fuze for the dual-purpose

improved conventional munitions. Batteries aren't its

primary business, but the company found it more

convenient to make its own power source for the M234.

"We make batteries now, because I could not find a

good supplier that met my needs," said Eric Guerrazzi,

president of KDI, which is part of L3 Communications. "I

got into the business totally in self defense, because I

can't deliver fuzes without batteries."

"Everyone who had any expertise in batteries left the

defense market and went to cell phones and computers,"

said Guerrazzi. "Those that are left are scraping by

with no incentive to improve their products."

While Harsch doesn't believe the industry is in bad

shape, he does see areas where government intervention

could help.

"There

are tax incentive programs they could look at, or of

course just out-and-out better pricing."

"There

are tax incentive programs they could look at, or of

course just out-and-out better pricing."

Munitions batteries come with unique requirements not

found in any other industry. They must be capable of

lying dormant on a shelf for 20 years, and then

discharge their power in a fraction of a second. They

must function in temperatures ranging from minus 45

degrees F to a steamy 145 degrees F, and withstand being

fired out of a cannon that subjects them to as many as

100,000 Gs [the force of gravity].

Batteries that power munitions often are as small as

pencil erasers. The M234/235 self-destruct fuze, used in

the dual-purpose improved conventional munitions

grenades, has the smallest battery in any current U.S.

system. It's only 0.13 cubic centimeters, and consumes

20 to 25 micro- liters of electrolyte. Most munitions

batteries are larger, with the one powering Multi-Option

Fuze for Artillery using 2.5 milliliters in a battery

that is 19 cubic centimeters.

Doug Troast, who leads guidance system development

for the Excalibur, blamed changing requirements rather

than battery problems for delays in the program. He said

Excalibur's designers paid careful attention to

batteries from the start. "If the battery doesn't work,

then nothing else does."

But Goldberg isn't confident that munitions designers

are getting the message. "They have a way of developing

a system and it's pretty well set, and it would take a

radical change of thinking to treat batteries

differently.